Coding Bootcamp Claims: The truth behind the numbers – National Consumers League

They promise valuable skills, new careers, and higher salaries. They offer convenient and flexible schedules. But at the end of the day, for-profit schools are just businesses…and it’s all too easy for clever marketing to come between prospective students and realistic expectations.

A string of high-profile school closures has plagued the for-profit education sector for the past several years, including the 35,000-student ITT Educational Services, and all 28 campuses run by Corinthian Colleges. Unfortunately, a string of incidents suggest that some coding bootcamps may be following the same pattern. Though there have been some promising developments in the area of educator accountability, for the most part, graduation rates and job placement statistics remain uneven, confusing, and sometimes downright misleading.

Lack of transparency

At first glance, most coding schools boast impressive numbers. The outcomes page of the average bootcamp usually features impressive names and numbers, spanning world-class companies like Facebook, LinkedIn, Amazon, Capital One, and Paypal. Bootcamps often post sky-high job placement and graduation rates hovering above 90 percent.

Unfortunately, what are most impressive aren’t the statistics themselves—but the creative and sometimes diversionary formula used to create them. Few schools are audited by third-party organizations—a critical step to proving an institution’s credibility—and a 2016 survey by the International Business Times found that of 11 major coding bootcamps investigated, only one had its results verified by a third-party auditor. The survey criticized these schools for making little effort to substantiate what claims they made, such as by failing to disclose student completion rates, job placement rates, or both. These concerns were echoed in a 2016 assessment by the San Francisco Chronicle, which found serious discrepancies in the 2015 numbers for several schools.

One problem in particular—selection bias—has been found to be a serious problem with bootcamp claims. Without the presence of a third-party auditor, schools can choose to exclude groups of students at will, especially those who enroll without US residency and citizenship (but who pay the same rates as their American peers). Stretching the criteria for “personal emergency” is another tactic used to hide the graduates who are unable to find jobs.

In 2015, ten bootcamps sent a letter to then-President Obama, promising that they would commit and adhere to clearer standards in coding education. Among their commitments were disaggregating information—by ethnicity, religion, gender, and veteran status—breaking down how long it took various numbers of students to find jobs, and determining an accurate average salary among graduates.

Two years later, the first such initiative—which focuses on setting standards and defining responsible reporting—is now here. Seventeen schools have joined forces to form the Council on Integrity in Results Reporting (CIRR). Members include well-known schools, but it’s worth noting that the newly founded group does not include many other well-known bootcamps.

Still, the CIRR methodology is a big step forward, mainly because it emphasizes clear communication (results must be compiled in a single, clear report), stringent standards, and regular auditing. CIRR’s reporting requirements address in detail the statistical problems that have long plagued bootcamps. Notably, graduate job placement numbers must be broken down into categories like full-time, part-time, internship, apprenticeship, and entrepreneur.

Only time will tell whether the CIRR is as effective as it aims to be, but it is without a doubt a step in the right direction. In the absence of effective government intervention (the California-based Bureau for Private Postsecondary Education being a notable exception) the only consumer protection in the coding bootcamp industry comes from what is essentially a self-regulating industry group. And the CIRR, well-intentioned as it may seem, is not explicitly set up to assist consumers, even those enrolled in its member institutions. Instead, its main goal is to set standards for subscribing bootcamps—and in the process, boost these schools’ public image.

Though CIRR is a good start, the scope of its oversight is limited and its motivations are perhaps not entirely neutral. Until coding bootcamps are thoroughly regulated and vetted like traditional institutions of higher education, coding bootcamps may continue to have a suspect reputation in the minds of many prospective students.

here’s no doubt that humans love chocolate. Globally, we consume

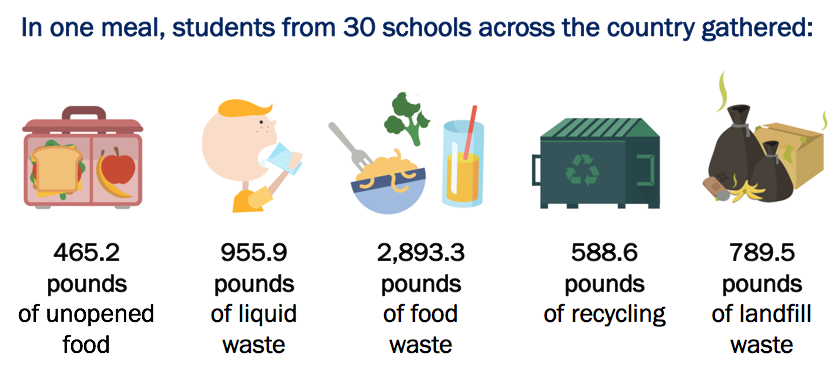

here’s no doubt that humans love chocolate. Globally, we consume  Instead of throwing away unopened food, it could have been recovered or donated. The potential for food rescue is detailed in the table below. Amounts were calculated using

Instead of throwing away unopened food, it could have been recovered or donated. The potential for food rescue is detailed in the table below. Amounts were calculated using