2021 rings in new health care protections for consumers

By NCL Director of Health Policy Jeanette Contreras

By NCL Director of Health Policy Jeanette Contreras

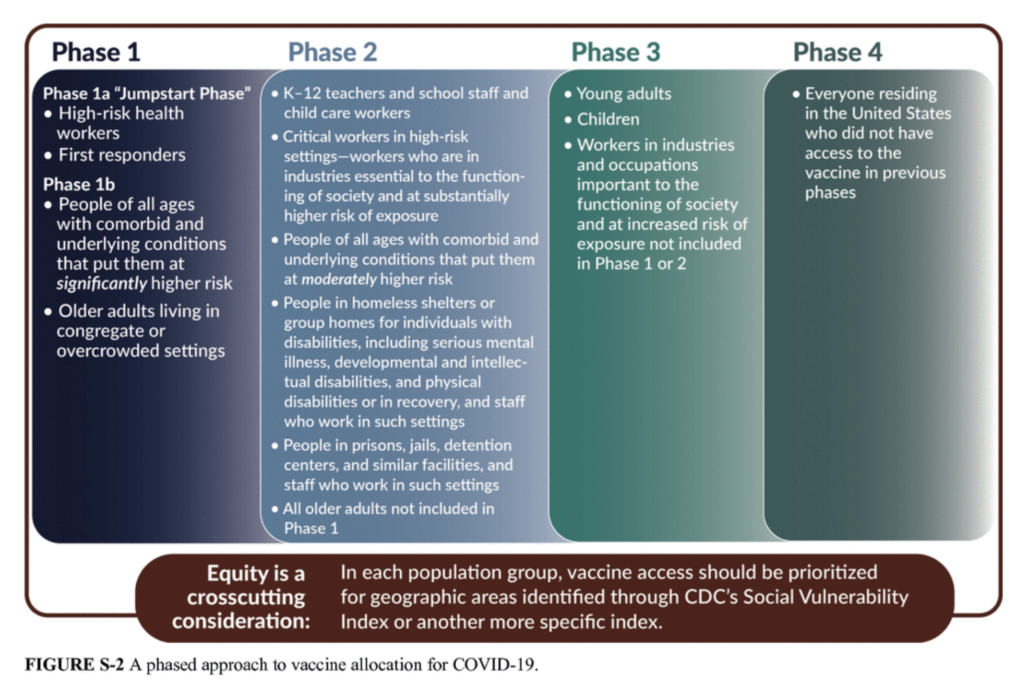

Surprise medical bills occur when patients unknowingly receive care from a provider who is not in their health insurance plan’s network. As the first COVID-19 vaccinations are administered, Congress has passed landmark legislation to ensure consumers needn’t worry about surprise medical bills from emergency medical services.

The passage of this legislation couldn’t come soon enough, as more than 476,000 Americans hospitalized with the coronavirus have already incurred exorbitant medical debt from COVID-19 treatment. Now, thankfully, 2020 will come to a close with renewed optimism in the American health care system.

This new law will also protect consumers from surprise billing from out-of-network ambulance and air ambulance trips, which can amount to tens of thousands of dollars in medical bills. Most patients are conscientious consumers, careful to find a doctor that accepts their insurance before making an appointment. However, in the case of an emergency, a patient faces the possibility of receiving care from an out-of-network doctor in an out-of-network hospital.

As Congress debated legislative fixes to surprise billing, the Administration showed political will toward finding a solution with the issuance of Executive Order 13877, Improving Price and Quality Transparency in American Healthcare to Put Patients First, which includes principles on surprise billing. In a *July 2020 report addressing surprise billing, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) further urged Congress to act, recognizing that 41 percent of insured adults nationwide were surprised by a medical bill in the past two years.

Following Executive Order 13877, HHS finalized a *set of regulations to address price transparency for consumers. The first rule set to take effect on January 1, 2021, requires hospitals to publicly list standard charges for the items and services that they provide. The second rule, set to take effect in 2022, demands similar transparency from most health plans and issuers of health insurance coverage. These regulations offer consumers more control over their health care spending and better information as they shop and compare health coverage options for themselves and their families.

The new HHS regulations, coupled with the surprise billing legislation, amount to the greatest consumer protections in America’s health care system since the Affordable Care Act. Consumers with health insurance should not have to worry about surprise medical bills—especially during a pandemic. The health care system will be a little more consumer-friendly in 2021, which is good news for all of us.

*Links are no longer active as the original sources have removed the content, sometimes due to federal website changes or restructurings

By Nailah John, Linda Golodner Food Safety and Nutrition Fellow

By Nailah John, Linda Golodner Food Safety and Nutrition Fellow