A lesson in sautéing up nutrition: the coconut oil debacle – National Consumers League

Last week, a Harvard professor made headlines after calling coconut oil “pure poison.” I can’t help shaking my head at such an outlandish statement. The idea that foods can cause cancer—or the opposite, that one superfood can cure disease—is a false claim we see time and again in news. We see it particularly in headlines, serving as “clickbait.” Food is neither a pure poison nor a panacea.

Last week, a Harvard professor made headlines after calling coconut oil “pure poison.” I can’t help shaking my head at such an outlandish statement. The idea that foods can cause cancer—or the opposite, that one superfood can cure disease—is a false claim we see time and again in news. We see it particularly in headlines, serving as “clickbait.” Food is neither a pure poison nor a panacea.

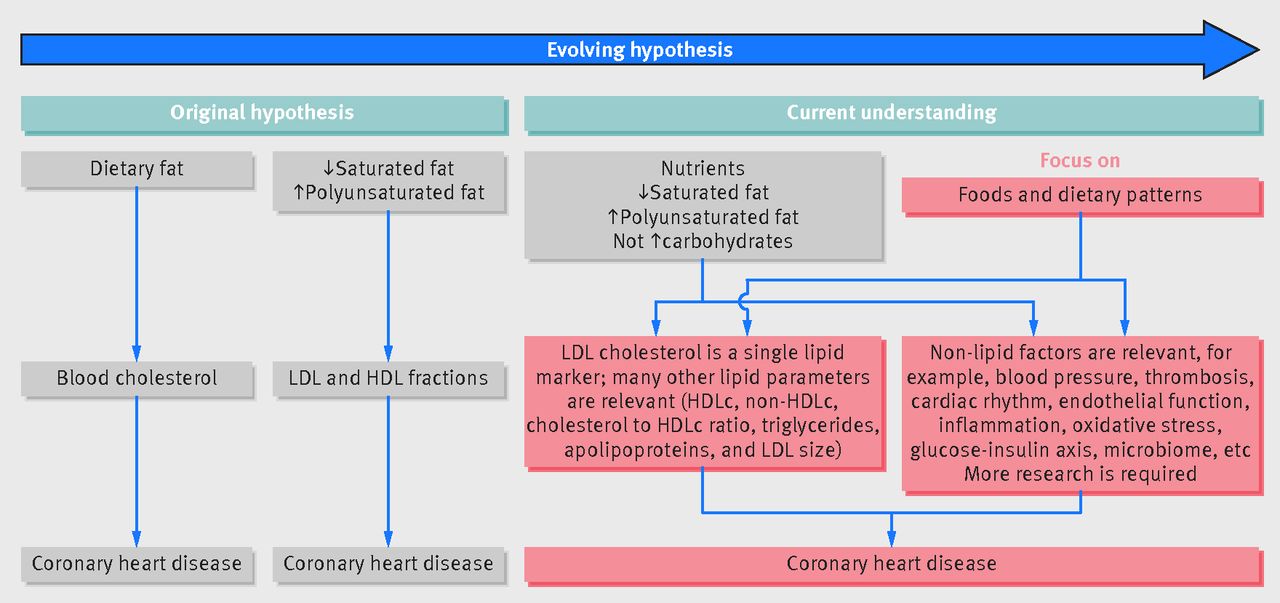

Like the many food “scandals” before (remember 2015’s bacon-gate?), the coconut oil debacle does reflect substantial data on its potential dietary fat harms. Before describing the data on coconut oil, it’s necessary to describe changes in the study of dietary fat over the last few years. In June, the British Medical Journal published a consensus statement on dietary fats. The image below from BMJ captures the evolution of the relationship between nutrition science, dietary fat intake, and heart disease. Essentially, eating foods high in saturated fats is not what causes high LDL (the “bad” blood cholesterol) or coronary heart disease—what most people had thought for decades. Instead, it’s a combination of nutrients, dietary intake, and other health conditions that lead to heart disease.

Amid these developments, consumers gained unprecedented access to new cooking oils in the food marketplace. It is now commonplace to see avocado, cottonseed, groundnut, and other vegetable oils alongside canola and olive oils in the grocery store; and the growth in demand is even stronger in Asian countries. Globally, the market is expected to grow by 5.5 percent from 2017 to 2026, representing $65 million annually.

As the market boomed, researchers began testing the differences in the nutritional profiles between the many new varieties of cooking oils available for mass consumption. Coconut oil stood out, high in saturated fat content and, coincidentally, touted by many media influencers as a cure all to everything from skin and hair care and as an alternative to canola oil for frying foods.

Several longitudinal studies found that coconut oil raised LDL to levels similar to those found in butter, beef fat, and palm oil. In 2017, the American Heart Association awarded coconut oil a presidential advisory warning against its consumption. Alternatively, coconut oil also has the lowest polyunsaturated fat among the many varieties of cooking oil—a mere 2 percent, as compared with the 78 percent of safflower oil.

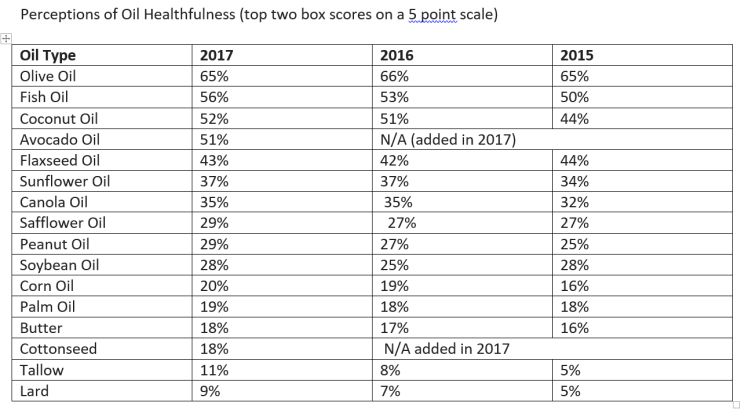

But authors reporting on the coconut-oil-is-poison story seemed surprised at the notion that the popular item could be detrimental to health. This makes sense, given that we—broadly as consumers—generally think coconut oil is … healthy. According to Cargill’s annual FATitudes survey (see table below), perception of coconut oil healthfulness grew from 44 percent in 2015 to 52 percent in 2017. At the same time, canola oil—tying with olive oil for first place in monounsaturated fat levels, which is linked to HDL (the “good” cholesterol in the bloodstream)—hovered around 35 percent.

The good news is that any consumption of vegetable oils seems to be preferable to animal cooking sources (e.g., lard, butter, or red meat). As the cooking oils market continues to grow, we must do a better job at reducing the power of clickbait. Flashy headlines should not take the place of facts.